On Friday, September 27, 1861, a contentious cabinet meeting was held in General Winfield Scott's office with Major General George McClellan attending. The main topics were the war and the inactivity of McClellan's army. There was a general feeling that the war should have been over by now and most present wanted to know why it wasn't. McClellan was still training and drilling his green recruits into a fighting force and would not be ready to move for several more months.

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Sunday, September 25, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Naval Contrabands

On Wednesday, September 25, 1861, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles laid out the naval policy on contrabands in a command to Flag Officer Samuel Du Pont, commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

"The Department finds it necessary to adopt a regulation with respect to the large and increasing number of persons of color, commonly known as 'contrabands.' now subsisted at the navy yards and on board ships-of-war. These can neither be expelled from the service, to which they have resorted, nor can they be maintained unemployed, and it is not proper that they should be compelled to render necessary and regular services without compensation. You are therefore authorized, when their services can be made useful, to enlist them for the naval service, under the same forms and regulations as apply to other enlistments. They will be allowed, however, no higher rating than 'boys,' at a compensation of ten dollars per month and one ration per day."

Thursday, September 22, 2011

150 Years Ago -- The Raid on Osceola

On Sunday, September 22, 1861, Kansas Jayhawkers, led by James Lane, a radical abolitionist, raided the town of Osceola, Missouri. No military advantage was gained; it was a senseless two-day spree of looting, arson and drinking, just another chapter in the sordid guerrilla war along the Kansas-Missouri border. Several pro-Southern citizens were executed in the town square.

When the raid was over, Lane's jayhawkers looted the town of everything they could carry and burned the rest. The once prosperous town of 2500 was reduced to just 200 inhabitants and never again would have as many people as it did before the raid.

When the raid was over, Lane's jayhawkers looted the town of everything they could carry and burned the rest. The once prosperous town of 2500 was reduced to just 200 inhabitants and never again would have as many people as it did before the raid.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Lincoln Orders Fremont to Modify Emancipation Proclamation

On Wednesday, September 11, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln wrote to Major General John Frémont in St. Louis ordering him to modify his August 30 proclamation to the people of Missouri.

The general had declared:

On August 6, Lincoln had signed a Confiscation Act into law. This act allowed for the confiscation only of those "persons held to service" who were "employed in hostility to the United States." The act did not free the confiscated slaves. Their status was left undefined, presumably for Congress to decide at some future time. Lincoln found Frémont's emancipation proclamation to be dictatorial, far beyond the power of any general in the field. At this point, he was trying to limit the war to the question of preserving the Union. He asked Frémont to modify the order to conform with the Confiscation Act; the general refused. Now Lincoln was through asking:

Also on September 11, 1861, in Kentucky, the legislature passed a resolution calling on Governor Beriah Magoffin to order Confederate troops to leave the state. Another resolution calling for both armies to leave was defeated.

The general had declared:

"The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, and who shall be directly proven to have taken active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use; and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free."

On August 6, Lincoln had signed a Confiscation Act into law. This act allowed for the confiscation only of those "persons held to service" who were "employed in hostility to the United States." The act did not free the confiscated slaves. Their status was left undefined, presumably for Congress to decide at some future time. Lincoln found Frémont's emancipation proclamation to be dictatorial, far beyond the power of any general in the field. At this point, he was trying to limit the war to the question of preserving the Union. He asked Frémont to modify the order to conform with the Confiscation Act; the general refused. Now Lincoln was through asking:

WASHINGTON, D.C., Sept. 11, 1861,

Major-Gen. John C. Fremont:

SIR: Yours of the 8th, in answer to mine of 2d inst., was just received. Assuming that you upon the ground could better judge of the necessities of your position, than I could at this distance, on seeing your proclamation of Aug. 30, I perceived no general objection to it; the particular objectionable clause, however, in relation to the confiscation of property, and the liberation of slaves, appeared to me to be objectionable in its non-conformity to the act of Congress, passed the 6th of last August upon the same subjects, and hence I wrote you expressing my wish that that clause should be modified accordingly. Your answer just received, expresses the preference on your part that I should make an open order for the modification, which I very cheerfully do. It is therefore ordered that the said clause of said proclamation be so modified, held and construed as to conform with and not to transcend the provisions on the same subject contained in the act of Congress, entitled "An act to confiscate property used for insurrectionary purposes, approved Aug. 6, 1861," and that said act be published at length with this order. Your obedient servant,

(Signed) A. LINCOLN.

Also on September 11, 1861, in Kentucky, the legislature passed a resolution calling on Governor Beriah Magoffin to order Confederate troops to leave the state. Another resolution calling for both armies to leave was defeated.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Proclamation (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Lincoln Writes to Fremont (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Reply to Lincoln (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- The Confederate Army Invades Kentucky (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Grant Occupies Paducah (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Abraham Lincoln,

John Fremont,

Kentucky,

Missouri,

slavery

Saturday, September 10, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Jessie Fremont's Audience with the President

On Tuesday, September 10, 1861, Jessie Benton Frémont arrived in Washington to plead her husband's case for his August 30 emancipation proclamation.

John Frémont, commander of the Western Department, had issued a proclamation declaring martial law in the state of Missouri, but he had gone further, promising to free the slaves of anyone found to be in rebellion against the United States. There was also the matter of threatening to shoot anyone who was found guilty by a court-martial "who shall be taken with arms in their hands within these lines."

Lincoln had written to Frémont urging the general to modify his proclamation. He saw it as dictatorial, far beyond any authority a general in the field might have. The proclamation threatened to expand the war; Lincoln was trying to keep the war a simple matter of preserving the Union. Freeing slaves would have a disastrous effect on the war effort, alienating Northern Democrats and the few slave states that were still in the Union, especially Kentucky.

Frémont took six days before replying to Lincoln. He refused Lincoln's suggestion to modify the proclamation -- "If I were to retract of my own accord it would imply that I myself thought it wrong and that I had acted without the reflection which the gravity of the point demanded. But I did not. I acted with full deliberation and upon the certain conviction that it was a measure right and necessary and I think so still." He would only modify the proclamation if ordered to do so by Lincoln.

Now Mrs. Frémont was in Washington to plead her husband's case. Jessie Benton Frémont was the daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton. She was no stranger to Washington and had met with most of the leading politicians of the day. This trip would not be a pleasant one though.

After a tiring, two-day journey by train, she arrived at the Willard Hotel late in the evening of September 10 and sent a message to the White House, inquiring as to when she might meet with the president. The reply was surprising: "Now, at once. A. Lincoln." Mrs. Frémont hurried to the White House. Lincoln met her in the Red Room. He was standing and did not offer her a seat. She presented the general's letter. Lincoln "smiled with an expression that was not agreeable" and read it.

"(B)oth voice and manner made the impression that I was to be got rid of briefly...In answer to his question, 'Well?' I explained that the general wished so much to have his attention to the letter sent, that I had brought it to make sure it would reach him. He answered, not to that, but to the subject his own mind was upon, that 'It was a war for a great national idea, the Union, and that General Frémont should not have dragged the negro into it. -- that he never would if he had consulted with Frank Blair. I sent Frank there to advise him.'"

When Mrs. Frémont began to make the argument that emancipation would keep England and France from recognizing the Confederacy, Lincoln cut her off, noting "in a sneering tone," "You are quite a female politician."

Lincoln's side of the story was almost as equally unpleasant. He told his secretary John Hay,

"She sought an audience with me and tasked me so violently with so many things, that I had to exercise all the awkward tact I have to avoid quarreling with her. She more than once intimated that if Gen. Frémont should conclude to try conclusions with me he could set up for himself."

The next day, Mrs. Frémont met with Francis Blair, a longtime friend. He scolded her, "Who would have expected you to do such a thing as this, to come here and find fault with the President?" He later added, "Look what Frémont has done; made the President his enemy!"

Also on September 10, 1861, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston was appointed commander of the Western armies, commanding troops in Tennessee, Missouri, Arkansas and Kentucky.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Proclamation (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Lincoln Writes to Fremont (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Reply to Lincoln (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Friday, September 09, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Lincoln Writes to David Hunter

On Monday, September 9, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln wrote to Major General David Hunter, requesting that the general go to St. Louis to assist Major General John Frémont in administering the Western Department.

From his vantage point some 800 miles away, Lincoln felt that the situation in Missouri was getting out of hand and that Frémont was in over his head as commander of the department. Frémont had spent some $12 million to arm and equip his command, and as is usually the case when vast sums are spent in a big hurry, graft and corruption was rampant. The headquarters was too lavish and Frémont was too isolated within it. The military situation was unraveling after the defeat at Wilson's Creek; guerrilla warfare was becoming all too common. On top of everything else, the president was displeased with Frémont's emancipation proclamation.

Many of these negative reports were coming from the Blair family. One of the leading families in Missouri, the Blairs had urged the general's appointment, but had quickly fallen out with him.

David Hunter had graduated from West Point in 1822 and had been in the U.S. Army some 30+ years. In early 1861, concerned for Lincoln's safety, he had volunteered to join the party escorting the president-elect to Washington for his inauguration. Soon after the Civil War began, Hunter had been appointed colonel of the 3rd U.S. Cavalry, but just three days later had been promoted to brigadier general. Commanding the 2nd Division of General Irvin McDowell's army, Hunter had been severely wounded at the Battle of Bull Run. On August 13, he was promoted to major general.

Lincoln felt that Hunter could best assist Frémont as his chief of staff, but Hunter's rank was too high for Lincoln to order him to take the position. On September 9, Lincoln wrote to Hunter:

Hunter quickly agreed and set off for St. Louis, arriving there on September 13. Instead of chief of staff, Frémont would make him a division commander.

From his vantage point some 800 miles away, Lincoln felt that the situation in Missouri was getting out of hand and that Frémont was in over his head as commander of the department. Frémont had spent some $12 million to arm and equip his command, and as is usually the case when vast sums are spent in a big hurry, graft and corruption was rampant. The headquarters was too lavish and Frémont was too isolated within it. The military situation was unraveling after the defeat at Wilson's Creek; guerrilla warfare was becoming all too common. On top of everything else, the president was displeased with Frémont's emancipation proclamation.

Many of these negative reports were coming from the Blair family. One of the leading families in Missouri, the Blairs had urged the general's appointment, but had quickly fallen out with him.

David Hunter had graduated from West Point in 1822 and had been in the U.S. Army some 30+ years. In early 1861, concerned for Lincoln's safety, he had volunteered to join the party escorting the president-elect to Washington for his inauguration. Soon after the Civil War began, Hunter had been appointed colonel of the 3rd U.S. Cavalry, but just three days later had been promoted to brigadier general. Commanding the 2nd Division of General Irvin McDowell's army, Hunter had been severely wounded at the Battle of Bull Run. On August 13, he was promoted to major general.

Lincoln felt that Hunter could best assist Frémont as his chief of staff, but Hunter's rank was too high for Lincoln to order him to take the position. On September 9, Lincoln wrote to Hunter:

"Gen. Fremont needs assistance which it is difficult to give him. He is losing the confidence of men near him, whose support any man in his position must have to be successful. His cardinal mistake is that he isolates himself, & allows nobody to see him; and by which he does not know what is going on in the very matter he is dealing with. he needs to have, by his side, a man of large experience. Will you not, for me, take that place? Your rank is one grade too high to be ordered to it; but will you not serve the country, and oblige me, by taking it voluntarily?"

Hunter quickly agreed and set off for St. Louis, arriving there on September 13. Instead of chief of staff, Frémont would make him a division commander.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Proclamation (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Lincoln Writes to Fremont (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Abraham Lincoln,

David Hunter,

John Fremont

Thursday, September 08, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Reply to Lincoln

On Sunday, September 8, 1861, Union Major General John Frémont replied to President Lincoln's "request" to modify his emancipation proclamation.

Frémont, commanding the Department of the West, had issued a proclamation on August 30, declaring martial law throughout the state of Missouri. Lincoln had problems with the third paragraph which went further than the Confiscation Act recently signed into law:

Lincoln, who just then was trying hard to keep Kentucky in the Union, wrote to Frémont on September 2, asking the general to modify his proclamation. Frémont finally replied on September 8:

In addition to sending the letter, Frémont sent his wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, to Washington to plead his case. She would arrive in Washington on September 10.

Frémont, commanding the Department of the West, had issued a proclamation on August 30, declaring martial law throughout the state of Missouri. Lincoln had problems with the third paragraph which went further than the Confiscation Act recently signed into law:

All persons who shall be taken with arms in their hands within these lines shall be tried by court-martial, and, if found guilty, will be shot. The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, and who shall be directly proven to have taken active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use; and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free.

Lincoln, who just then was trying hard to keep Kentucky in the Union, wrote to Frémont on September 2, asking the general to modify his proclamation. Frémont finally replied on September 8:

HEADQUARTERS WESTERN DEPARTMENT,

Saint Louis, September 8, 1861.

The PRESIDENT.

MY DEAR SIR: Your letter of the 2d by special messenger I know to have been written before you had received my letter, and before my telegraphic dispatches and the rapid development of critical conditions here had informed you of affairs in this quarter. I had not written to you fully and frequently, first, because in the incessant change of affairs I would be exposed to give you contradictory accounts; and, secondly, because the amount of the subjects to be laid before you would demand too much of your time.

Trusting to have your confidence I have been leaving it to events themselves to show you whether or not I was shaping affairs here according to your ideas. The shortest communication between Washington and Saint Louis generally involves two days and the employment of two days in time of war goes largely toward success or disaster. I therefore went along according to my own judgment leaving the result of my movements to justify me with you.

And so in regard to my proclamation of the 30th. Between the rebel armies, the Provisional Government and home traitors I felt the position bad and saw danger. In the night I decided upon the proclamation and the form of it. I wrote it the next morning and printed it the same day. I did it without consultation or advice with any one, acting solely with my best judgment to serve the country and yourself and perfectly willing to receive the amount of censure which should be thought due if I had made a false movement. This is as much a movement in the war as a battle, and in going into these I shall have to act according to my judgment of the ground before me as I did on this occasion. If upon reflection your better judgment still decides that I am wrong in the article respecting the liberation of slaves I have to ask that you will openly direct me to make the correction. The implied censure will be received as a soldier always should the reprimand of his chief. If I were to retract of my own accord it would imply that I myself thought it wrong and that I had acted without the reflection which the gravity of the point demanded. But I did not. I acted with full deliberation and upon the certain conviction that it was a measure right and necessary and I think so still.

In regard to the other point of the proclamation to which you refer I desire to say that I do not think the enemy can either misconstrue or urge anything against it, or undertake to make unusual retaliation. The shooting of men who shall rise in arms against an army in the military occupation of a country is merely a necessary measure of defense and entirely according to the usages of civilized warfare. The article does not at all refer to prisoners of war and certainly our enemies have no ground for requiring that we should waive in their benefit any of the ordinary advantages which the usages of war allow to us. As promptitude is itself an advantage in war I have also to ask that you will permit me to carry out upon the spot the provisions of the proclamation in this respect. Looking at affairs from this point of view I am satisfled that strong and vigorous measures have now become necessary to the success of our arms; and hoping that my views may have the honor to meet your approval,

I am, with respect and regard, very truly, yours,

J. C. FRÉMONT.

In addition to sending the letter, Frémont sent his wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, to Washington to plead his case. She would arrive in Washington on September 10.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Proclamation (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Lincoln Writes to Fremont (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Abraham Lincoln,

John Fremont,

Missouri,

slavery

Wednesday, September 07, 2011

150 Years Ago -- McClellan Goes Ballooning

Image of Thaddeus Lowe via Wikipedia

Image of Thaddeus Lowe via WikipediaOn September 7, 1861, Union Major General George McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, went ballooning with Thaddeus Lowe.

Lowe had been posted near Arlington, Virginia, at Fort Corcoran since his balloon was completed on August 28. He conducted aerial reconnaissance and took several generals, reporters and artists aloft. Just two days before McClellan's first flight, Lowe had gone aloft with Generals Irvin McDowell and Fitz John Porter.

McClellan observed the Confederate fortifications at nearby Munson's Hill and Clark's Hill, and got a view of Washington similar to this one that appeared in the July 27, 1861 edition of Harper's Weekly. It is unclear how many flights McClellan made, but he saw the value of the balloon as a military asset, and Lowe soon received an order to construct four more balloons and purchase portable gas generators.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- Establishing a Balloon Corps (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago: Ballooning (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

George McClellan,

Thaddeus Lowe

Tuesday, September 06, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Grant Occupies Paducah

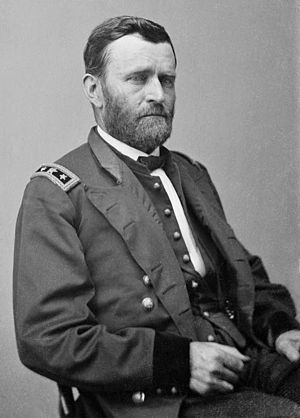

Image of Ulysses S. Grant via Wikipedia

Image of Ulysses S. Grant via WikipediaOn Friday, September 6, 1861, Union troops under Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant occupied Paducah, Kentucky, at the confluence of the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers, without resistance. This move was in response to the Confederate occupation of Columbus, Kentucky on September 3.

Kentucky's neutrality would have been violated in any case. Major General John Frémont, the commander of the Union Department of the West, had ordered Grant to occupy Columbus as soon as possible. While Confederate Major General Leonidas Polk didn't know about those orders, he had beaten Grant to the punch, but had unleashed a firestorm in Kentucky against the Confederacy by invading the state first.

Grant issued a proclamation to the people of Kentucky:

"I have come among you not as an enemy, but as your fellow-citizen. Not to maltreat or annoy you, but to respect and enforce the rights of all loyal citizens. An enemy, in rebellion against our common Government, has taken possession of, and planted its guns on the soil of Kentucky, and fired upon you. Columbus and Hickman are in his hands. He is moving upon your city. I am here to defend you against this enemy, to assist the authority and sovereignty of your Government. I have nothing to do with opinions, and shall deal only with armed rebellion and its aiders and abettors. You can pursue your usual avocations without fear. The strong arm of the Government is here to protect its friends and punish its enemies. Whenever it is manifest that you are able to defend yourselves and maintain the authority of the Government and protest the rights of loyal citizens I shall withdraw the forces under my command."

Polk's invasion of Kentucky was a major political blunder, but he also committed a strategic blunder. He had planned to occupy Paducah as well, but had moved too slowly and let Grant take the town. With Columbus, the Confederates could block the Mississippi with their big guns on the high bluffs, but Grant's occupation of Paducah gave the Federals another avenue for a Southern invasion: the Tennessee River. Grant would soon occupy Smithland, opening up the Cumberland River as well.

Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin would demand that both sides withdraw from Kentucky soil, but the state legislature would demand that only the Confederates withdraw, and would invite the Federals to give the state "that protection against invasion which is granted to each one of the states by the fourth section of the fourth article of the Constitution of the United States."

Magoffin vetoed the resolution, but both houses overrode the veto. The General Assembly declared its allegiance to the Union and ordered the United States flag to be raised over the state capitol.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- The Confederate Army Invades Kentucky (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Grant Takes Command at Cairo (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Kentucky,

Leonidas Polk,

Ulysses S. Grant

Monday, September 05, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Foote Arrives in St. Louis

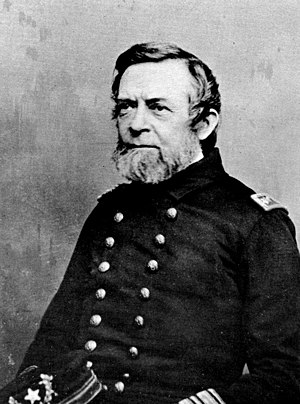

Image of Andrew Foote via Wikipedia

Image of Andrew Foote via WikipediaOn Thursday, September 5, 1861, Captain Andrew Foote arrived in St. Louis to take command of the Federal naval forces on the upper Mississippi. Foote superseded Commander John Rodgers. Foote would later work closely with General Ulysses S. Grant in combined army/navy operations on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers.

Foote briefly attended West Point in 1822, but left to accept an appointment as a midshipman at Annapolis. He had a reputation as a fighter. During the Second Opium War, in the Battle of the Pearl River Forts in Canton, China, in 1856, Foote led a landing party of 287 men. They captured one fort and used the captured guns to attack and capture another fort. Then, with the help of the blockading ships, they fought off a counterattack by some 3000 Chinese soldiers and captured two more Pearl River forts.

Rodgers would head east to serve under Flag Officer Samuel Du Pont in the Port Royal Expedition in October. He would served in the U.S. Navy until his death in May 1882. At that time he was the Navy's oldest active rear admiral.

Also on this date, President Abraham Lincoln met with General Winfield Scott. The main topic of conversation was what to do about John Frémont, the commander of the Department of the West, who was becoming more of a headache for the administration with each passing day.

At Cairo, Illinois, General Ulysses S. Grant was looking to counter the Confederate position at Columbus, Kentucky. He recognized the important of Paducah, at the confluence of the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers, and formed an expedition to occupy the town. The troops left that evening. Grant informed Frémont of his intentions, but had the troops in motion before receiving a reply.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- Grant Takes Command at Cairo (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- The Confederate Army Invades Kentucky (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Proclamation (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Andrew Foote,

John Fremont,

John Rodgers,

Ulysses S. Grant

Sunday, September 04, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Grant Takes Command at Cairo

Image of Ulysses S. Grant via Wikipedia

Image of Ulysses S. Grant via WikipediaOn Wednesday, September 4, 1861, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant arrived in Cairo, Illinois, to take command of the Union forces there. Cairo was an important position near the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. It was Grant's first major command of the war.

Grant was appointed to the position by General John Frémont, the commander of the Department of the West. Frémont was a career officer in the U.S. Army, but he had come up and achieved nationwide fame through the Topographical Corps. If he had been a member of the West Point clique, he probably would not have chosen Grant for this important assignment.

Grant had been typed as a drunk and a drifter. At West Point, he developed a reputation as a poor student with bad study habits. He graduated in 1843, ranked 21st out of 39 cadets. He fought in the Mexican War, winning brevets for gallantry at Molino del Rey and Chapultepec, but after the war was posted at several remote garrisons where he fought boredom and loneliness by drinking. He resigned in 1854.

In civilian life, he moved from one failed venture to another. At one point, he was reduced to peddling firewood on the streets of St. Louis. When the war began, he was able to gain a position as colonel of the 21st Illinois Infantry only because Elihu Washburne, an influential congressman, took a liking to him.

Frémont also took a liking to him, describing him as as a man of "unassuming character not given to self elation, of dogged persistence, of iron will." It would be one of the best decisions of Frémont's troubled time in St. Louis. Grant arrived at Cairo and quickly began looking to counter the Confederate's position at nearby Columbus, Kentucky.

Also on this date, at Columbus, Confederate Major General Leonidas Polk issued a proclamation to the people of Kentucky, declaring that he had moved into Kentucky and occupied the town in order to protect it:

"The Federal government having, in defiance of the wishes of the people of Kentucky, disregarded their neutrality by establishing camp depots of armies, and by organizing military companies within her territory, and by constructing military works on the Missouri shore, immediately opposite and commanding Columbus, evidently intended to cover the landing of troops for the seizure of that town, it has become a military necessity, for the defence of the territory of the Confederate states, that the Confederates occupy Columbus in advance. The major-general commanding has, therefore, not felt himself at liberty to risk the loss of so important a position, but has decided to occupy it in pursuance of this decision. He has thrown sufficient force into the town, and ordered to fortify it. It is gratifying to know that the presence of his troops is acceptable to the people of Columbus, and on this occasion he assures them that every precaution shall be taken to insure their quiet, protection to their property, with personal and corporate rights."

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- The Confederate Army Invades Kentucky (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Proclamation (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

John Fremont,

Kentucky,

Leonidas Polk,

Ulysses S. Grant

Saturday, September 03, 2011

150 Years Ago -- The Confederate Army Invades Kentucky

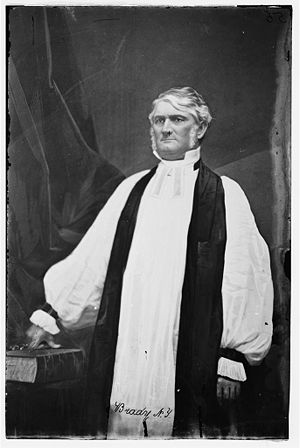

Image of Leonida Polk via Wikipedia

Image of Leonida Polk via WikipediaKentucky's position of neutrality in the Civil War was doomed to fail. It finally came to an end on Tuesday, September 3, 1861, when Confederate troops under Brigadier General Gideon Pillow crossed into the state from Tennessee to occupy Columbus. The troops soon placed guns on the high bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River.

The move was ordered by Pillow's superior, Major General Leonidas Polk. He feared the Federals were planning to occupy the town and was trying to beat them to the punch. He would soon announce that he had occupied the town to protect it.

Polk was correct in his assessment of the situation. The Federals were massed across the river in Missouri, and Major General John Frémont had ordered Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant to occupy Columbus as soon as possible.

Polk had signaled his intentions in a letter to pro-secessionist Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin on September 1: "I think it of the greatest consequence to the Southern cause in Kentucky or elsewhere that I should be ahead of the enemy in occupying Columbus and Paducah." When the troops were in motion, Polk wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis to tell him what he had done and why.

Pro-Unionist Kentuckians protested, but the greatest protests came from Tennessee Governor Isham Harris. As long as Kentucky could stay out of the war, it would act as a shield protecting Tennessee from invasion. Harris wrote to Confederate Secretary of War LeRoy Walker, who ordered Polk to withdraw immediately, but Davis countermanded the order, telling Polk that "the necessity justifies the action."

Friday, September 02, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Lincoln Writes to Fremont

On Monday, September 2, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln wrote to Major General John C. Frémont regarding the general's August 31 proclamation to the people of Missouri.

Lincoln ordered Frémont not to shoot any prisoners without his (the president's) authorization. Lincoln feared that Frémont's threat that "all persons who shall be taken with arms in their hands within these lines shall be tried by court-martial, and, if found guilty, will be shot" would lead to the Confederates executing any prisoners they had taken in retaliation.

Lincoln did not order, but strongly suggested that Frémont modify his emancipation proclamation. In his letter, Lincoln said that he believed the proclamation "will alarm our Southern Union friends and turn them against us; perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky."

Kentucky, with its divided population, was still pursuing a policy of neutrality, and both sides were still tip-toeing around that neutrality, recruiting, arming and training men from the state, but avoiding overt acts that might push the state toward the opposing side. Lincoln feared that making the war about slavery would be just the thing to push Kentucky into the Confederacy.

Lincoln also feared that this proclamation would have an adverse affect on the slave states that were still in the Union and the Northern Democrats who were helping to fight the war.

On August 6, Lincoln had signed a confiscation act into law. This act, which passed the House 60-48 and the Senate 24-11, permitted the confiscation of any property, including slaves, that was used to support the Confederacy. The act stripped owners of their slaves, but left the status of the slaves unresolved. For the time being, they would be the property of the Federal government. Lincoln suggested that Frémont modify his proclamation to conform to the confiscation act.

Lincoln's letter to Frémont:

Lincoln ordered Frémont not to shoot any prisoners without his (the president's) authorization. Lincoln feared that Frémont's threat that "all persons who shall be taken with arms in their hands within these lines shall be tried by court-martial, and, if found guilty, will be shot" would lead to the Confederates executing any prisoners they had taken in retaliation.

Lincoln did not order, but strongly suggested that Frémont modify his emancipation proclamation. In his letter, Lincoln said that he believed the proclamation "will alarm our Southern Union friends and turn them against us; perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky."

Kentucky, with its divided population, was still pursuing a policy of neutrality, and both sides were still tip-toeing around that neutrality, recruiting, arming and training men from the state, but avoiding overt acts that might push the state toward the opposing side. Lincoln feared that making the war about slavery would be just the thing to push Kentucky into the Confederacy.

Lincoln also feared that this proclamation would have an adverse affect on the slave states that were still in the Union and the Northern Democrats who were helping to fight the war.

On August 6, Lincoln had signed a confiscation act into law. This act, which passed the House 60-48 and the Senate 24-11, permitted the confiscation of any property, including slaves, that was used to support the Confederacy. The act stripped owners of their slaves, but left the status of the slaves unresolved. For the time being, they would be the property of the Federal government. Lincoln suggested that Frémont modify his proclamation to conform to the confiscation act.

Lincoln's letter to Frémont:

WASHINGTON, D.C., SEPTEMBER 2, 1861

MAJOR-GENERAL FREMONT.

MY DEAR SIR:--Two points in your proclamation of August 30 give me some anxiety.

First. Should you shoot a man, according to the proclamation, the Confederates would very certainly shoot our best men in their hands in retaliation; and so, man for man, indefinitely. It is, therefore, my order that you allow no man to be shot under the proclamation without first having my approbation or consent.

Second. I think there is great danger that the closing paragraph, in relation to the confiscation of property and the liberating slaves of traitorous owners, will alarm our Southern Union friends and turn them against us; perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky. Allow me, therefore, to ask that you will, as of your own motion, modify that paragraph so as to conform to the first and fourth sections of the act of Congress entitled "An act to confiscate property used for insurrectionary purposes," approved August 6, 1861, and a copy of which act I herewith send you.

This letter is written in a spirit of caution, and not of censure. I send it by special messenger, in order that it may certainly and speedily reach you.

Yours very truly,

A. LINCOLN.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Proclamation (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- Becoming the Party of Freedom (opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Abraham Lincoln,

John Fremont,

Kentucky,

Missouri,

slavery

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)